The Impregnation of an Object: Roger Hiorns in conversation with James Lingwood, July 2008

How did you arrive at the idea of working with crystallisation?

It’s a bit like a childhood memory, I can see parts of it more than the whole. A while ago, maybe 10 years, I needed a material to achieve a certain kind of detached activity, and on a basic level an act of transformation, a material which was going to simply transform another material. I felt a system of nature like crystallisation would do.

What kind of control did you want over this transformation?

I was very interested in the idea that the artwork would exist aesthetically without my hand, and in not being present for most of the making. I would put together some kind of basic structure which would then grow into something else, the unanticipated other.

So working with crystallisation seemed to solve the problem of style, of the position of style being a static moment. Once people accept it, then it tends to stay with you rather than with anyone else, it builds a cave around you.

The object is made by the reaction that happens over time, these materials are introduced to each other, that was interesting to me, instead of processes like welding, sawing and, importantly, hammering … I like the idea of sculpture as slow object-making.

A slow process gives you the chance to stand back?

I am completely objective about my own artwork, I can stand outside of it, against the world, and work out whether it should exist or not. That’s why I use materials which enable me to become detached, materials which are their own thing, have their own genetic structure. Rather like copper sulphate is described as autogenetic, my work is also autogenetic, it tries to make some sense of my psychological position.

Fissure

by Brian Dillon

On a first visit in August 2008, some weeks before the work is left to its own occulted and alchemical devices, the site of Roger Hiorns’s Seizure looks already as though it encloses a secret of sorts. A modest cloister of late-Modernist design, the flat complex on Harper Road is half-hidden behind a bruise-purple hoarding, its upper storey flaking as if unused to the sunlight, the whole rising to no more than tree height among buildings of more ambitious upward thrust and implacable, unreadable aspect. The block of flats directly across the road has its entrances turned away from the traffic; scaffolding fronts the hundred or so dwellings that loom over the site on the other side. It seems decidedly interstitial: a human-scale development insinuated, almost as an afterthought, among the starker experiments in social housing. The complex turns in upon itself, sheltering its (now departed) community against the chaos of the city.

It is not only because of its late abandonment, or the knowledge of its forthcoming demolition, that once seen from inside the fence the structure seems to open up, to disarticulate into its skeletal components of concrete, glass and steel. Rather, one has the sense immediately of a place in process, not so much derelict (despite the boarded doors and windows, the plaques of rust and spalled concrete) as half-built and heading towards an as yet uncertain future. A kind of reverse archaeology is under way. Over on the left, at the busiest point, certain strata of the building have been stripped away and already replaced with alien materials, such as the metal mesh that will support the crystals. The interior is being mined for a secret that does not yet exist.

This essay was also published in the book Roger Hiorns: Seizure.

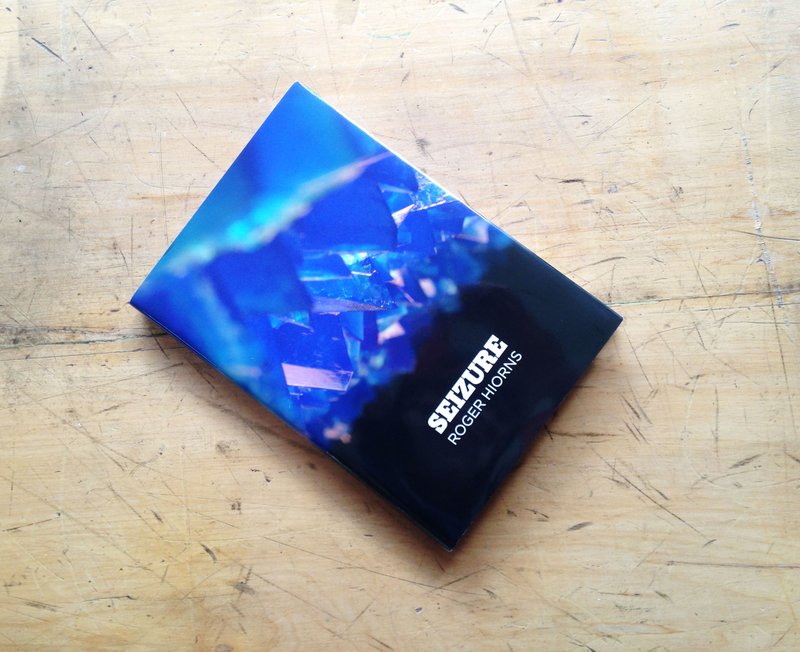

Seizure

Out of print.

… the facets, fissures and unexpected, almost vegetal, protuberances of the crystal surface appear to expose the space to its outside; the crystalline perplex becomes part of the architecture of the flat complex and its environs, causing the planes and surfaces of concrete and brick to flex and fracture and rearrange themselves into novel attitudes and estranging patterns. — Brian Dillon, Fissures (an essay)

This book comprises essays by Brian Dillon, JJ Charlesworth, Tom Morton and a conversation between James Lingwood and Roger Hiorns, alonside photography and extensive research and archival material.

- Published by Artangel

- Designed by Anne Oldling-Smee, O-SB

- Edition of 1,500, 111pp

- Hard cover

- 245 x 170 mm

- ISBN: 9781902201214

Signs of Life

By JJ Charlesworth

There has been work going on. Standing on the access balcony of the small block of habitation units on Harper Road, one can look across the grass and the tarmac path towards the large habitation unit called Symington House. Symington House is a tower block, and it is under scaffold. It was completed in 1958, and now, in 2008, it is undergoing renovation. The scaffolding structure partly obscures the façade of the building, its white-painted concrete and windows obstructed by the scaffold’s spindly greyish lines and wooden decking, installed at each floor level. But a clear view of the building is hindered by the sheets of blue plastic netting hung from level to level to prevent debris falling to the ground. This blue sheeting hangs like a veil, a screen of cold colour that turns the light-welcoming windows of Symington House into dark, blank squares, dimly glinting, impenetrable.

There is no work going on now. The access decks of the scaffold are not empty, however. There are objects on these decks, but these are not the tools or equipment that would be used for the business of renovation. These are domestic objects; a child’s bicycle, a bedside chest of drawers, an ironing board, some exercise equipment. They punctuate the decks at irregular intervals, in little clusters outside one or other of the apartments in the block. They are moments of surplus activity, excesses emanating from the body of the building, currently wrapped in its lattice of grey scaffold and its skin of perforated blue plastic…

This essay was also published in the book Roger Hiorns: Seizure.

Roger Hiorns

Roger Hiorns was selected as part of the 2006 Open call for proposals from Artangel and Jerwood, creating Seizure in 2008. He was a member of the judging panel for both the 2013 Open and 2014 Open.

Roger Hiorns has developed a singular body of work over the past decade. He introduces unusual materials to found objects and urban situations to create surprising new forms. Born in Birmingham in 1975 and now based in London, Hiorns has exhibited extensively in museums and galleries in Europe including at: Art Now at Tate Britain, London (2003), UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2003), Milton Keynes Gallery, Milton Keynes (2006), Glittering Ground, Camden Arts Centre, London (2007), as part of the British Art Show 6 (2005), Destroy Athens 1st Athens Biennial, Athens (2007) and A Life Of Their Own, Lismore Castle Arts, Co Waterford, Ireland, (2008). Hiorns was shortlisted for the 2009 Turner Prize.

Images: (above) Roger Hiorns in 2008. Photograph: Gautier Deblonde. (Left) Roger Hiorns inside Seizure in 2008. Photograph: Nick Cobbing.

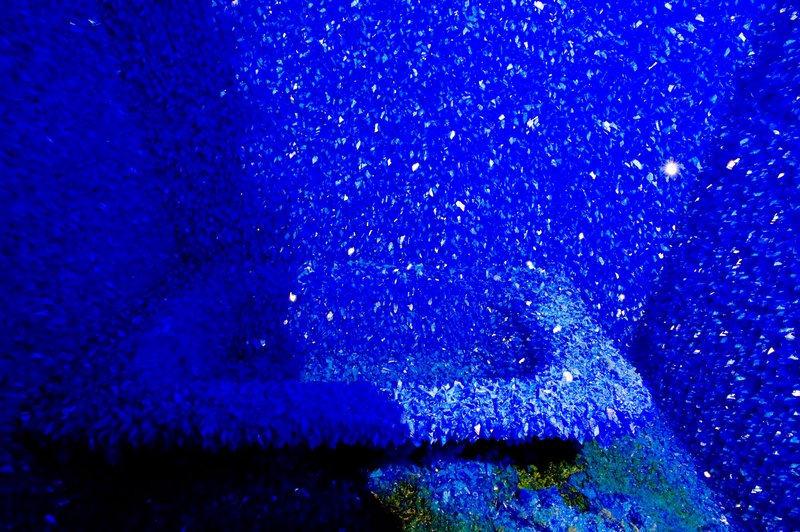

… today [Hiorns and his assistants] are beginning to siphon out the 90,000 litres of bright blue, super-saturated copper-sulphate solution (enough to fill a large swimming pool) that for two-and-a-half weeks has been cooling in a metal tank lining the entire volume of one of the ground-floor bedsits. When all the liquid is emptied and the metal tank cut away, there should be a thick growth of copper sulphate crystals covering the walls, floor and ceiling, but at this stage even Hiorns isn’t entirely sure what, if anything, will be revealed. — Helen Sumpter, Time Out, 4 September 2008

I could have plummeted thousands of fathoms beneath the sea into Neptune's grotto, or sauntered into a nightclub with clusters of crystals forming wonky glitter balls. Alice tumbling down the rabbit-hole into Wonderland could hardly have felt more bemused or beguiled. — Alastair Sooke, The Daily Telegraph, 3 September 2008

[Seizure] is destined to be remembered as one of the truly worthwhile and significant moments of modern British art … The result is a mineral cavern inside a bereft flat, as if the inhabitant had magically created this beauty by force of will and dream. It invites you to make up a story about how this transformation occurred, to picture some strange life of tragedy and transcendence. — Jonathan Jones, The Guardian, 29 October 2008

Water oozes down the walls like a toxic sweat and gathers in the cracks of the uneven floor in dirty little puddles. Nestled in a crystalline nook, the bath tub – a solitary remnant of past human occupation – is jagged with sharp excrescences. Seizure feels claustrophobic and disturbingly unsafe: the wellie-and-glove-equipped visitors are trapped in noxious caves. It looks as if nature, on a furious whim, had fought back the excruciating boredom of regimented societies. — Coline Milliard, Art Monthly, October 2008

You imagine what it might be like to be trapped in there, the doorway grown over. You might somehow be slowly pulped by the advancing crystalline needles, until you were no more than an impurity at the heart of some massive rock formation. In the meantime, this small concrete, brick and plaster-board dwelling has become a bejewelled cave. And it is not actively frightening. The crystals cannot grow in air. You have time to get out. — Hugh Pearman, The Sunday Times, 9 November 2008 (behind paywall)

The installation drew more than 25,000 people to a soon-to-be-demolished housing complex near London Bridge. Only four people could enter the apartment at one time, so visitors stood in line for hours in a concrete courtyard as they waited to pull on rubber boots and see the crystalline cavern. — Bethany Halford, Chemical & Engineering News, 5 January 2009

Credits

Commissioned by Artangel and Jerwood Foundation, supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, in association with Channel 4. The work was selected through the Jerwood/Artangel Open, a new commissioning initiative for the arts, which was launched in the summer of 2006 in association with Channel 4 and Arts Council England.

This project was supported by Arts Council England, Artangel International Circle, Special Angels, Guardian Angels and The Company of Angels.